Break Down and Let It All Out

Crissi Cochrane

How Windsor songwriters deal with performing emotionally difficult material

One of the greatest things about being part of a creative community is the opportunity to have some amazing conversations about art. These talks usually happen in private, and I often find myself wishing that such conversations could be shared with a wider audience.

And so, when Travis Laver, an excellent singer-songwriter, activist, podcast host and teacher, posted on his Facebook page asking fellow songwriters to weigh in on the subject of performing songs that elicit strong emotions, I saw this as an opportunity to document and share one of these fascinating conversations.

“Question for songwriters: Have you ever written a song that you can't ever play because it hits too close to real emotions? Did you manage to play it eventually in front of people? How did that go?”

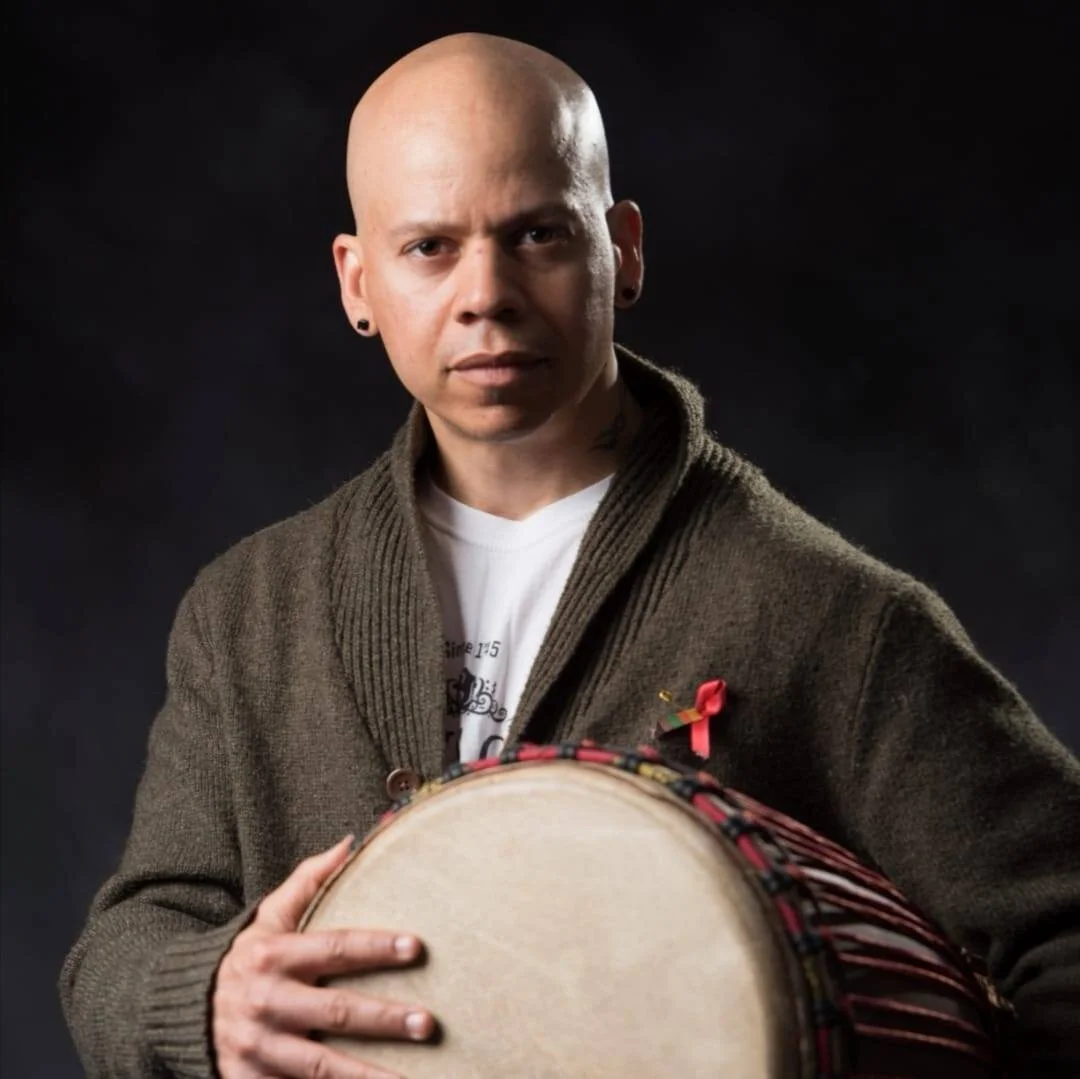

Travis Reitsma

He explained that he has one particular song that used to be too difficult to perform. He succeeded in overcoming the urge to break down and cry, only to have it return again after his grandfather’s passing. The song was his grandfather’s favourite.

In the comments, local musicians and writers weighed in on how they cope with performing emotionally-charged material, and the responses were beautiful. I was awed to learn how many fellow writers shared this struggle, and I’m delighted to have been granted permission to share with you the reflections of some fantastic Windsor artists.

Right away, Leighton Bain’s comment on the subject was a truth so perfect, I think I might want to have it framed:

“That song you think is too personal/difficult to play is probably the song that an audience member needs to hear from you to help them through a similar time in their life.”

Leighton Bain

Even though these kinds of songs are incredibly personal and intimate, you’d be hard-pressed to find any emotional subject that doesn’t resonate with listeners. That’s the beauty of the human experience: just as the popular children’s song says, we all sing with the same voice. These thoughts and feelings are universal. And as difficult as it can be to evoke pain, a song creates a safe space to explore it, and deepen the connection between a performer and a listener. It’s a loving exchange, and it’s why music has always felt like the closest thing to religion for me: sublime moments of harmony with other human beings, a communion of souls, the sharing of our burdens.

My label mate Max Marshall added his voice to the conversation, saying:

“If there’s a tune or musical situation that I can’t get through without losing it, during my private rehearsals/practice sessions, I’ll just not try to hold it back, and let the outpouring have its valve open to full, have a nice big cry, get it all off my chest, then take a deep breath and play the tune again. And again. If I keep welling up, I keep allowing it to come and have its full sorrowful way with me and eventually I’ll come to terms with it, just have it so off my chest, I can perform the song without having it crack me. Working through material that is painful for us is so therapeutic in the end, but sure forces us to confront shit. I feel like it’s up to songwriters to never lose the evocation of emotion for our audiences to feel what we want them to feel, but it’s totally up to us to have come to terms with our subject matter and like sociopaths, have the mental distance to the material to be able to get through it.”

Max Marshall

It endeared me to think of Max, this beautiful human being, weeping out his sorrows this way. There’s a nobility to these art forms, confronting our demons so that we can help others do the same. Remember this, the next time art as a career path needs defending.

It’s astute of him to mention the almost sociopathic nature that’s necessary to get through some of our material without breaking down - I feel like this nature was inherent in me when I first started making music. I was a huge fan of emo, and every song was laced with heartbreak, pain, and bitterness. It was the status quo, and with my good childhood free of trauma, I could visit these dark spaces without really understanding them at all. I would write my own emotionally-charged songs and deliver them again and again with complete impassivity - until time passed.

Case in point: my song “Coming Home”, from my first full-length album, Darling Darling (2010). Inspired by a visit to my hometown shortly after moving away, the song points out all the landmarks of my own personal history with the town, from my childhood home, to the overpass where I drank as a teenager, to the home of a friend who passed away suddenly in grade 12, and the bus station where my mother and I cried when I moved away. I sang this song for years without trouble, but when my style shifted into more soulful territory, I stopped playing it, and stopped recalling those memories altogether. When my mother asked me to play the song for our family and friends at Christmas in 2016, it had been several years since my mind had gone back to those places, and I completely crumbled in front of everyone and had to stop before the end. (My voice tends to fall apart if I begin crying, and I often physically can’t get words out at that point.)

Another explanation is that maybe I’m just getting more sentimental. And I was relieved to discover that I’m not the only one - radio personality and champion of local music Dan MacDonald commented:

“I can’t speak for songs but I have a poem about a fire I was involved in - and I can’t read it in public without a severe emotional voice crack. As I get older I am more emotional - so it ain’t getting any better.”

Dan MacDonald

Multidisciplinary artist, activist, and director of contemporary Arts centre Artcite Teajai Travis weighed in, too:

“I've written spoken word pieces like that. The result is the emotions hit double when shared in front of an audience.”

Teajai Travis

Sharing evokes the perspectives of everyone present, and invites you to experience the piece as the performer and the listener, all at once - Teajai is so right; the feeling is so much stronger with an audience. Sometimes, that can make the song so much more difficult to execute, exploring those hard places and feeling vulnerable and exposed; sometimes, it makes it easier, knowing that the audience is there to learn from you, to catch you if you stumble, and to experience something through you. It’s an opportunity to guide them - and yourself - to consolation.

Finally, I weighed in too:

“I’ve had a lot of these over the years. Honestly, sometimes I just try think of something else if I feel like I’m on the edge of cracking - something mundane, like what’s for dinner or the chores I have to do later, and if that doesn’t work, then I think about politicians that I hate, haha. (That usually works really well.) Sometimes that moment of raw emotion is right at the end of a song, so I just muscle through, knowing that the ending is right there - and maybe I’ll sound a bit strangled for a note or two, but then when the song ends, I can just say “ah, that song just really gets to me” and wipe away my tears and laugh at myself a little, take a deep breath, sip my drink, and move on to the next song. I personally would love to see any artist have a moment like that in a set - I think showing vulnerability that way is just amazing, and I would probably feel my heart explode with such a fierce love for that person, for going there.”

As much as it can be a struggle to perform these difficult songs, I’ve learned that the urge to break down can be a good indication of whether or not I’m on the right track. Many of the great singer-songwriters I admire from the East Coast - especially Rose Cousins - have that ability to evoke tears (in fact, Rose has a t-shirt design that proudly declares, “Rose Cousins Made Me Cry”). Storytelling was front-and-centre in the music made around me in the Maritimes, and I find myself tapping into those roots more and more as I get older.

Rose Cousins (Photo by Lindsay Duncan)

On a similar note, my husband and I have had a lot of conversations recently about how to deliver emotional subject matter in songs - not simply how to endure the performing of it, but how emotional the narrator should be in doing so, if controlling their emotions is within their ability. He cites the Woody Guthrie song “1913 Massacre,” about the tragic death of striking miners and their families in the Italian Hall disaster in Calumet, Michigan. Guthrie delivers the song with with an even and almost journalistic tone, as a third-party observer might do: as though he is an instrument channelling the story, and not injecting his own emotional response to the story in his telling of it. He leaves room for the listener to have their own reaction. I feel that this is similar to what Rose Cousins achieves - in her songs that move me the most, it’s her words and cadences that carry the expression. Her performances display a mastery of technique and are delivered powerfully, but without theatrics; each story is like a shared illusion, and she does nothing that might compromise its suspension, or break the spell.

On the opposite side of the spectrum is the inimitable Nina Simone, from whose catalogue I’ve borrowed the title of this piece. Nina was perhaps one of the most accomplished at emoting powerfully in music, and I maintain that her recording of “Ne Me Quitte Pas” is the most devastatingly heartbreaking performance on recording I have ever heard. There are moments where her despair shines through - when she sings the words “ne me quitte pas”, it sounds so forlorn and pleading. I can barely even listen to it without crying, and I doubt I will ever be able to perform it myself.

Nina Simone

Whether you deliver your work with composure or while struggling to maintain it, the burden of your obligation as a performer is to evoke emotions, some of which are unfairly imprisoned but have little other recourse to escape. What other therapy can be done in such a beautiful, harmonious way?

And so, I will leave you with the words of the great Nina Simone, who understood the performer’s obligation quite well:

“What I was interested in was conveying an emotional message, which means using everything you've got inside you sometimes to barely make a note, or if you have to strain to sing, you sing.”